As a writer, vintage clothing has a special value: there are stories embedded in the seams, memories embedded in the lining, caught between the pleats and hidden in the hem. Sometimes the previous owner has left evidence: a shopping list in their pocket, a coffee stain or a tear from an ecstatic night of dancing. An imperfection is an indelible detail of the charm of a used garment. A tear or missing button can tell the story of the item’s origin, and sometimes an imperfection explains how the item found its way to you, who will mend it and love it again. It’s true of humans too – our marks and scars tell the stories of where we’ve been, where we’ve fallen and how we’ve recovered.

For thousands of years, people wore each other’s clothes and bought and sold second-hand clothing because it was too expensive to buy new. My grandmother made the dresses my mother wore to school, then my aunt wore them, and then they were passed down to a cousin. But at some point, this tradition of resignation stopped being so common. Buying new clothes was a way of presenting oneself as self-respecting; the only people who wore vintage clothing were either poor or weird or both.

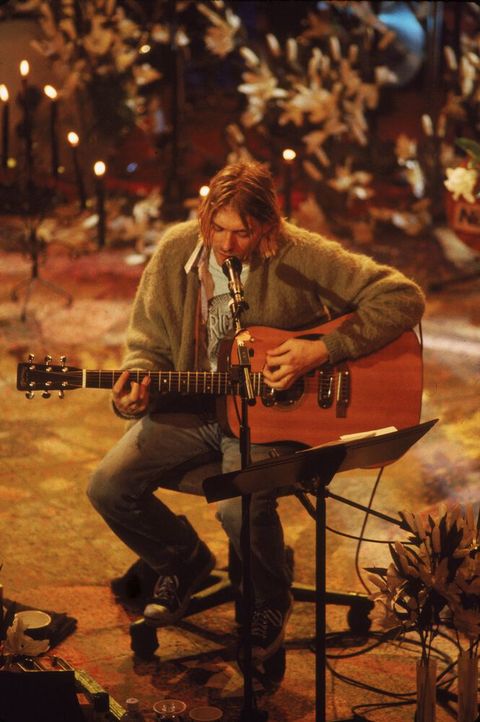

But then countercultures struck a fashion chord: Diggers in 1960s San Francisco put together spectacular outfits from discarded and donated clothing as part of their radical anti-capitalist lifestyle. Then London punks stepped even further, mixing clothing from all eras into a new aesthetic intended to make a person look like they’d just survived a trip to hell and back. The new look came into mainstream culture through television and movies. After that, goth and grunge took over the nineties. As a teenager in 1993, I saw Kurt Cobain singing live on television in a tattered green sweater, and my world changed forever. Cobain represented nonconformity, strength in honest vulnerability, and beauty that could be destroyed by its own rage and passion and still be beautiful. Grunge spoke to the nihilistic artist in my broken little teenage heart. Everyone I grew up with wore clothes from the same stores: Umbro football shorts, canvas trainers. I wasn’t a normal person, and vintage clothing was how I confirmed that.

Most of what I collected came from a vintage clothing store in Cambridge, Massachusetts called The Garment District. In the nineties, you could still find tea dresses from the 20s and polyester print shirts from the seventies in mountains of clothes selling for a dollar a pound. I’d sit in a pile and go through the clothes, getting an adrenaline rush as I pulled on a flared sleeve and found a patterned dress, or I’d discover in a pile of destroyed jeans a perfect pair of Levi’s 501s that had graffiti all over them personalized on knees, reading ‘Class of ’76’. At the time, I wasn’t thinking about the ethical virtues of buying vintage. I was buying vintage to challenge the status quo. And dressing in vintage was a visual art; I saw it as a fashion collage. Sorting through the piles at The Garment District, I wasn’t looking for a quality staple that I could wear year after year: I was looking for something special that I felt like I was destined to find.

Wearing vintage clothing made me feel more at home and connected to the people of the past in this country where my family had just arrived. I was born in Boston, the first in my family to call the USA my home. My ancestors are Croatian and Persian, but New England has always felt rooted in my bones. By dressing in the clothes of the people who lived there before me, I was weaving their stories into my own.

The rise of vintage clothing to everyday wear seems to be a recent phenomenon, born of privilege and nostalgia as much as necessity, but a different need these days. Affordable clothing is ubiquitous and toxic to the environment. During its life cycle, a pair of jeans releases over 33kg of CO2, equivalent to driving around 69 miles. And if you try to throw those jeans away, they can take up to a year to fully biodegrade – and that’s only if they’re 100% cotton. Synthetic fibers only make things worse. Getting dressed in the morning has never been so ethically charged – and people will judge you for it. Head-to-toe fast fashion only looks good for one day. And then? Recycling your clothes is a way to clear your conscience.

What a vintage-phile like me loves most is seeing new fashion icons bring together looks from the past. I think of Kaia Gerber wearing her supermodel mom Cindy Crawford’s classic Alaïa leather jacket, making the nineties young and chic again. Zendaya wore a strapless black and white number from Valentino’s SS92 collection on the red carpet, taking the look off Linda Evangelista and making it all her own – no small feat. And from day to day, we have Emma Chamberlain’s ‘massive savings releases’, where she explains how pieces from the 1990s and Noughties can be repurposed for a different time.

And while I think it’s important to clean out and reevaluate one’s wardrobe every once in a while, there are a few items in my closet that I’ll never part with: the blue hoodie I wore when I met my husband, the dress he wore my mother when. she lived in Brussels in the 1970s, wearing my late brother’s “I Climbed the Great Wall of China” t-shirt.

When I wear something vintage, I feel like a time traveler. The texture and weight of a garment on my body, the way it moves around me, the shapes it makes, all bring me back, as if it’s playing up a memory: what it felt like to be me, or someone else entirely.

When I sat down to write the show notes for Proenza Schouler’s AW22 collection, I couldn’t let go of the idea of fashion as a means of moving through time, as a way to reflect the values and fascinations of an era. Talking to the designers, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, about how they conceived their collection was like talking to a novelist or a filmmaker. They build worlds, imagine characters and how they move; they look at details from the past and revive them to say something different, as if creating a wardrobe for a woman not yet born. They seemed to be asking, ‘Where are we going? And how do the clothes we wear reflect who we want to become when we get there?’

A few months later, I walked the runway for Maryam Nassir Zadeh, an Iranian-American designer who I greatly admire. Aside from the nerves and the sudden clue of how to move my legs, I felt completely new on the catwalk. No one had worn these clothes, or even seen them. I was introducing myself to the world for the first time. There was something magical about it. On a typical day, I go about my life as if when my clothes don’t look right, if they hang or ride up, it’s because there’s something wrong with me – my shape, my size. But acting as a model for future fashion, I felt no such insecurities. I didn’t need to think about being the weirdo that I am inside. Maryam didn’t want me to wear makeup. Simple hair. I felt naked and exposed, and beautiful myself. It was as if no clothing, no vintage, was there to define me.

“Lapvona” by Ottessa Mosfegh is out now.