[ad_1]

From Louis XIV’s vision of Versailles to Balenciaga’s homage to the sari, Inspired by India explores how our textiles and crafts have influenced global design. But what is the line between cultural appropriation and appreciation?

From Louis XIV’s vision of Versailles to Balenciaga’s homage to the sari, Inspired by India explores how our textiles and crafts have influenced global design. But what is the line between cultural appropriation and appreciation?

The fashion industry has undergone a reckoning in recent years in which questions of appropriation or appreciation have become defining parameters when drawing inspiration from cultures, communities and crafts. So many things that would have gone unnoticed even 10 years ago now seem problematic: be it these white models dressed like tribals. gopis on the catwalks of Paris, or brands adopting the aesthetic of handmade block prints for mass-produced fast fashion. But the reduction of Indian communities and their symbols to “exotics” are products of a relatively recent history, belying the complexity of the country’s role in global fashion and luxury for millennia.

Today, the idea of European savoir-faire dominates the global geography of luxury. So it is all the more ironic to realize the extent to which Indian textile traditions and forms of dress have shaped the contours of this luxury – particularly through the histories of the textile trade and, more recently, the role of Indian embroidery in luxury provision. chains.

History shows that the superior craftsmanship of our textiles came with the associations of a country with a high order of life. Beautiful textiles from the courts of Shah Jahan, descriptions of which were transmitted by 17th-century travelers, are believed to have helped fuel Louis XIV’s absolutist ambitions and vision for Versailles. But the sheer depth and breadth of India’s contribution to global fashion began in Roman times and accelerated between the 16th and 18th centuries—playing a pivotal role in transforming ideas of gender, the body, comfort, and leisure in Europe and America.

A fitted ladies’ chintz jacket (1750) cut to display chintz imported from the Coromandel Coast. In the Netherlands in the 18th century, chintz jackets were popular for everyday use and worn as part of traditional costume | Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In Napoleonic France and through Jane Austen’s novels in Regency England, we see how the wearing of fine Indian muslin indicates the consumer’s status, taste and recognition. Such was the popularity of textiles like brightly painted chintz that France and England imposed decades-long bans on their import in the 18th century in order to protect their silk and woolen factories. However, the desire for these living textiles meant that despite heavy fines, they were smuggled in as contraband and kept in the privacy of the home.

With jewels, settings and stereotypes

Indian jewelery has also long inspired desire and envy. The erstwhile maharajas were bound to play the role of passive partners during the Raj, often required to dress in their elaborate finery to attend events such as the Delhi Durbars and to legitimize Queen Victoria as Empress of India. during the height of colonial rule. Perhaps this strain on auto-Orientalism led so many Indian princes to seek an alternative aesthetic to that exploited by the Raj.

Rajasthan Necklace (Cartier 2016) with an engraved 136.99 carat cushion-shaped emerald from Colombia | Photo Credit: Amélie Garreau, Cartier Collection

Disenfranchised, they sought self-expression in a modern language they could make their own. They flocked to jewelers in Place Vendôme, Paris, to restore their jewels. In turn, these commissions deepened Parisian jewelers’ knowledge and understanding of Indian jewelry and setting techniques. The Maharaja’s jewelery inspired a style that has become iconic of early 20th century jewellery: the blending of exquisitely carved Mughal jewels and the inevitable combinations of Indian colors with the elegant lines of Art Deco.

Now, the glittering fantasy world of the maharajas has been reclaimed as an aspirational form of heritage luxury for Indian consumers, especially in the mass wedding market. Closely associated with Bollywood and celebrity-driven wedding trends, some argue that this world of maharaja chic is so fantastical that it is beyond questions of appropriation. A similar argument has been made for many aspects of Indian culture, such as the paisley motif, which are the product of deep global entanglements where it is difficult to determine where one cultural imprint ends and another begins.

However, this way of thinking does not address how images and objects are often used in ways that may serve to reinforce certain stereotypes of India to the exclusion of other representations. Nor does it count the work behind its aesthetics, particularly the work of India’s artisans who embroider, embellish and weave some of the country’s most recognizable symbols of heritage and identity.

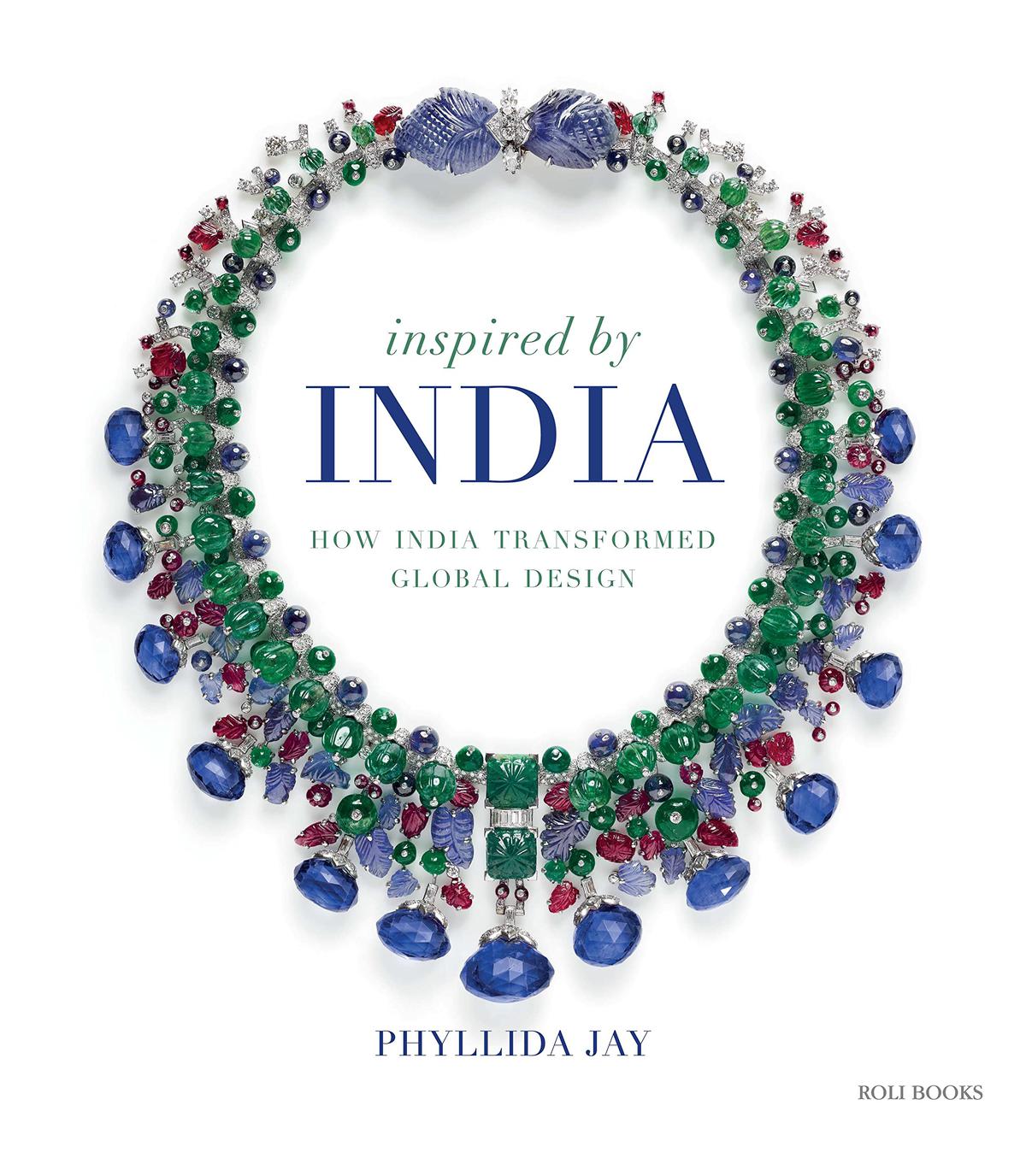

The cover of the book Inspired by India

All of this raises specific questions: how can India’s rich cultural heritage inform designers in ways that transcend reductive stereotypes and reward and recognize the communities and artisans on whom fashion and luxury so often depend? How can we overcome the limited and proprietary ideas of culture that are often hidden in debates about cultural appropriation? What can history, which spans the spectrum of appropriation, exploitation, colonial domination and transculturation, tell us about the present and, more importantly, the future?

When the curtain went up in Europe

IN Inspired by India, the chapter on the sari deals with one of India’s most enduring symbols. Its global representation has often dipped into the exotic, influenced in no small part by the quirky aesthetic of our greatest cultural export, Bollywood films. However, a more nuanced study of the sari reveals its role in inspiring radical approaches to the body through fashion by some of the most iconic designers of the 20th century. For example, Cristóbal Balenciaga studied the drape and interpreted it in an innovative and respectful way that paid homage to it. We see a similar depth of commitment in the work of Gianfranco Ferré and Madame Grès. This foreshadows the innovative work of designers like Tarun Tahiliani, Amit Aggarwal and Gaurav Gupta.

T. Venkanna’s Pencil and Hand Embroidery on Linen | Photo: Abhay Mascara; Artwork Copyright: T. Venkanna and Maskara Gallery

Now, a new generation of photographers like Ashish Shah, Prarthna Singh and Rid Burman are challenging stereotypical representations of India. When integrating Indian inspiration, many international brands are beginning to understand the importance of working with local creators. Some European luxury brands such as Dior have even begun to address the systematic invisibility of India’s top embroidery artisans in their supply chains and provide some visibility into the crucial role of Indian embroidery in European luxury.

A saree worn by designer Gaurav Gupta | Photo: Courtesy Gaurav Gupta

Pushing against the weight of history is not easy, but it is vital. A set of art embroidery images under the India Redux chapter showcases the collaborative work of artist T. Venkanna and artisans from the Kalhath Institute, a Lucknow-based non-profit organization dedicated to craft preservation and artisan education, founded in 2016 by Maximiliano Modesti. Playful and painterly, the embroidery art transcends the usual boundaries of this craft form and provokes new ways of seeing and appreciating the work of artisans. The Kalhath Institute offers a rigorous curriculum for talented young embroiderers, equipping them with the skills set to make the most of the opportunities offered by the 21st century markets. Following in their footsteps, the Mumbai-based Chanakya School of Crafts supported by Dior has used the work of artisans in collaborations between the brand and artists such as Manu and Madhvi Parekh.

Evaluation is about rigorous research and respectful engagement with another culture, and it’s also about investing enough time, study, and dedication to create innovations inspired by it, rather than reproducing stale clichés. It is also about crediting, compensating and supporting the communities and artisans on whose shoulders rests so much of India’s intangible cultural heritage. Every designer or brand should start from this base, when inspired by India.

Inspired by India: How India Transformed Global Designhas Phyllida Jay exploring the complex history of over six centuries of cultural exchange between India and the world. Published by Roli Books.

[ad_2]

Source link